Presidential elections are, by no means, a one-night event. Nor are the final results — the only time votes are counted. Pre-election polls start releasing predicted voting results months in advance, beginning what feels like a near-daily competition between presidential candidates. However, while pre-election polls may reveal important insights about the opinions of different voter demographics, such as by gender or race, they cannot definitively predict who will become president of the United States.

In fact, since the newspapers involved in pre-election polls face significant pressure to retain credibility, poll results are not necessarily representative even of their initial sample, let alone that of the American voting population. Polling predictions cannot deviate greatly from final election results, making it incredibly risky for newspapers to publish results heavily in favor of a particular party. Therefore, the safest course of action is to neutralize what they consider “unlikely” outcomes, weighting their results against those of past elections to bring them closer to a fifty-fifty split between the two candidates.

As more pollsters produce these “neutralized” results, the cost to a news organization of publishing anything different grows increasingly large, producing an incentive to stick with the crowd. Evidently, politics exists in polling too. Through this alone, it is clear that pre-election polls cannot necessarily tell us who the next president will be. But can they influence election results?

Experts in the field have speculated that polling may influence voters through the bandwagon effect, which causes voters to rally behind a candidate who is predicted to do well, or conversely, through the dampening effect, which discourages supporters of a predicted losing candidate from voting because the polls have convinced them that their vote will not matter. Neither of these effects were present in the 2024 election.

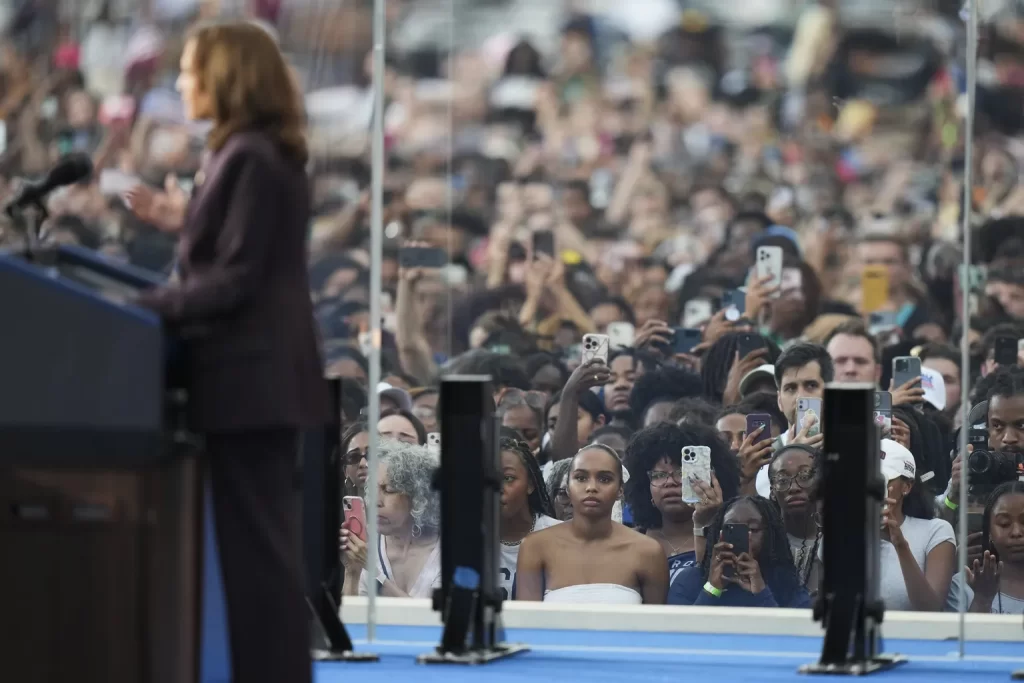

As expected, polls prior to the election showed a close split between those predicted to vote for Kamala Harris or Donald Trump, sometimes giving Harris a slight lead in many swing states. These results gave the impression of an incredibly close race for the presidency.

However, this turned out not to be the case: much of the country, including previously left-leaning states, moved rightward, and a large number of people didn’t vote at all— especially within groups who usually voted Democrat. While the fact that the polls did not predict a stark shift right fits the pattern of poll “neutralization,” it might also explain increased voter apathy.

When polls show the possibility of success for a candidate that a voter does not feel drawn to despite being of the party they otherwise would have voted for, they may lose their sense of responsibility to vote since they are comforted by the knowledge that others will do it for them. In some ways, this theory is a mix of both bandwagon and dampening effects: a candidate’s possible success discourages voters from casting a vote.

In the 2024 election, this effect would have disproportionately impacted Democrats. In recent years, Republicans have had a far more cohesive ideology than Democrats, since it seems the only unifying factor between progressives and moderates has been a desire for “anyone but Trump.” Democratic voters have been growing increasingly fatigued by this message.

For Republicans, this election was also seen as an existential matter because Trump’s use of doomsday messaging during his campaign convinced many of his voters that a Harris presidency would destroy the country. Democratic voters did not experience this sentiment to the same degree they did in the 2020 election where voter turnout rose by 7 percent in part from their desperation to remove then-President Trump from office. Pre-election polling showing a slight lead for Harris might have further reduced any remaining sense of desperation by giving Democratic voters a false sense of comfort.

Of course, it is impossible to solely blame pre-election polling for the Democrats’ loss, but it is important to consider what may have decreased voter turnout. The psychological effects of “neutralized” polling may be one place to start.

The Zeitgeist aims to publish ideas worth discussing. The views presented are solely those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial board.