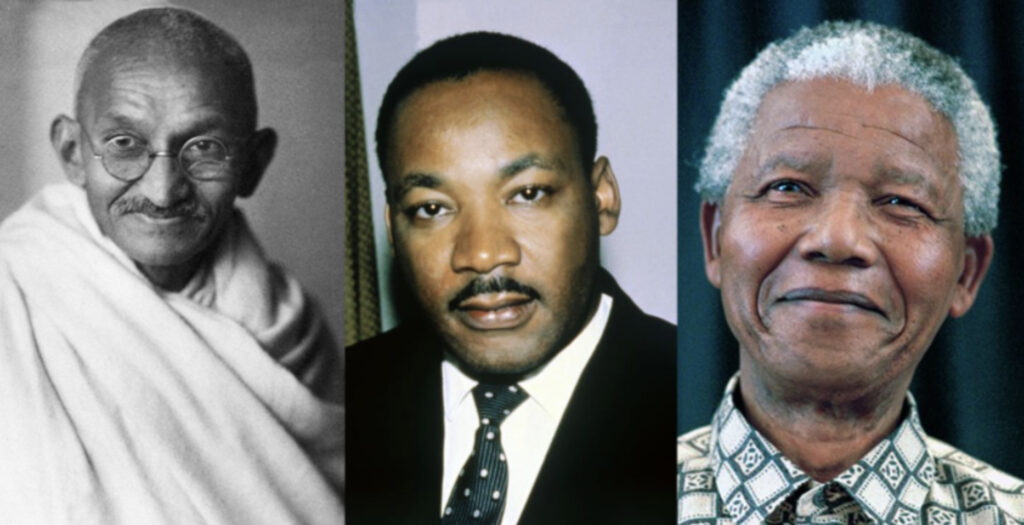

Nonviolence is often referenced in moments of social upheaval and unrest today. When anger broke out in the streets across America after the murder of George Floyd, political and media elites quoted Martin Luther King Jr. in attempts to curtail protesters. “In spite of temporary victories, violence never brings permanent peace”—a quote from King’s Nobel Lecture delivered in 1964—has been frequently cited in opinion articles and politicians’ rhetoric to condemn aspects of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Such reverence of nonviolence, however, is rarely done in good faith. It ignores the institutional violence that nonviolent protest intends to resist as well as the violence that is used to punish it. Instead, the ideology of nonviolent resistance is stripped of its historical nuances and motivations and instead used to undermine liberation movements today.

We often hear that King was a colorblind reverend who dreamed of “a nation where [people] will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” That because of this, he would have been appalled by Black Lives Matter and critical race theory.

King, however, also understood that the “riot is the voice of the unheard”. In his speech, “The Other America,” King cited the “intolerable conditions that exist in our society” as the root cause of violent protest, acts which he argues are desperate calls for attention from those that feel they have no other alternative. He wrote in his famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail that “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.” Yes, nonviolent strategy was a key component of the 1960s civil rights movement, but it did not call for passivity in the face of injustice.

King was once one of the most hated men in America. He was routinely called dangerous and an extremist by the FBI as well as White Americans for his nonviolent protest, which is today celebrated with a federal bank holiday. This whitewashing and sanitization of King’s character is not accidental. On the contrary, it is a systematic rewriting of radical history in order to maintain the facade of freedom, justice, and order that the world rests on today.

Mahatma Gandhi has undergone a similar process of veneration posthumously. In his anticolonial struggle against the British, Gandhi employed many nonviolent methods, including the Salt March of 1930, aiming to highlight the violence of colonialism. Indeed, he said that “violence is the weapon of the weak, non-violence that of the strong.” And yet, Gandhi was abhorred by many Britons, including Winston Churchill.

The liberation of the Indian subcontinent from colonial rule has long been used by Zionists against Palestinians who call for an end to the Israeli occupation of their homeland. Even those who feign sympathy for the Palestinian plight roundly denounce any and all forms of nonviolent resistance as antisemitism, such as the Boycott, Divest, and Sanction (BDS) movement. This ignores many realities, including the very real history of violence that ultimately led to Indian independence.

From the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 to Ghadar revolutionaries who worked to undermine British rule through targeted assassinations, violence was present in Indian resistance just as much as Gandian nonviolence was. In fact, historians such as Christopher Bayly and Ayesha Jelal have argued that the military threat presented by the Indian National Army, who aimed to secure independence, was directly responsible for the British exit from India in 1947.

However, much of this history has been forgotten, as the world invokes Gandhi’s name whenever there is some threat to Western institutions. Violence committed by the state is minimized as the acts of a few corrupt individuals, but even the concept of rebellion from the masses in response to oppressive state institutions is harshly condemned—even if they pose no real threat.

Nelson Mandela is yet another example of the co-opting of nonviolence by the state. Mandela was arrested numerous times and spent 27 years in prison for daring to challenge South African apartheid. Specifically, he was charged with incitement to strike and later for conspiring to overthrow the state. While Mandela is universally celebrated today as an advocate of nonviolent resistance, he was once seen as a terrorist and remained on the US terror watch list until 2008.

However, contrary to the aforementioned protest movement leaders, Mandela was not as staunchly in favor of nonviolence. He recognized nonviolence as “not a moral principle but a strategy; there is no moral goodness in using an ineffective weapon” in his autobiography Long Road to Freedom. When nonviolence failed to impart any practical change, Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) turned to carefully calculated acts of violence against the state.

Umkhonto, the ANC’s armed military wing, attacked South African government facilities in the 1960’s. The ANC, as a result, were openly labeled as a terrorist organization. Despite this, Mandela continued to organize resistance from his prison cell until the end of apartheid in 1990. Today, many have revised this tumultuous history as one of peaceful nonviolence. Moreover, boycotts and international pressure alongside these organized actions helped change public opinion until apartheid was untenable.

Like in India, the violence that was an integral part of the resistance movements has been largely ignored and forgotten. Just like King, Mandela today is heralded as a hero by those who would have very well condemned him when he was alive. This leaves us to question what violence is condoned as legitimate and what violence is deemed as terrorism, especially in this current moment of extreme violence. What is the difference between a riot and a rebellion? Why do some have the right to fight occupation, while others are expected to lay down and die?

Of course, nonviolence and civil disobedience have their values and merits. But when nonviolence fails to stop violence perpetrated by or upheld by our governments, how long are marginalized people meant to endure injustice? When nonviolence is weaponized against oppressed people to silence them, it becomes violent by perpetuating violent institutions. When protests, boycotts, and slogans are outlawed, this is violence.

Dr. King, Gandhi, and Mandela all dreamed of futures free of violence. But all of these men have become weapons of the very systems of racism and apartheid they criticized and sought to dismantle. It is a damning indictment of the nonviolence they preached, as we live in a world evermore embroiled in the violent oppression of the colonized peoples, orchestrated and justified by the leaders of the Western world.