Farming is the backbone of American agriculture. It provides the country with fruit and vegetables, but also with grains, oils, and animal feed. 97 percent of these farms are family-owned – by this definition, “family-owned” includes individual owners, family partnerships or family corporations. While this may come across as a higher percentage than expected, there is one lurking variable – the average age of these farmers is creeping up.

As of late 2022, the average farmer is nearly 60 years old. This age also continues to increase with each census, suggesting the issue continues to progress. Therefore, with the high percentage of farms in the U.S. that are family-owned, it is crucial that younger farmers are incentivized to begin farming and drive down the average age before we are left with a farming shortage.

However, the incentives to do so are currently slim. Agricultural workers make remarkably low wages compared to other industries – and are often bombarded with high-stress levels stemming from financing loans, volatile weather conditions, inconsistent yields and the time-consuming nature of the profession. Additionally, agricultural workers’ wages are not all accounted for in states’ minimum wages – in some states, agricultural workers are subject to be paid below the minimum wage. There are currently 20 states where this is the case.

With the cost of living and inflation rates rising, it makes sense that no one wants to get involved with farming. However, societally, we need to be thinking long-term about the stability of our food system. Agricultural workers are our food system’s backbone – without them, our supply dwindles and we are left with gaps in our supply chain.

How can we incentivize the younger generation to get involved with farming when the prospects are so bleak?

You may be familiar with the government’s military and college programs. Within these programs, those who serve in the military are eligible to havetheir tuition paid for by the federal government, as well as access to the G.I. Bill, which allocates about $36,000 in financial support for those formerly enlisted to invest in education and housing.

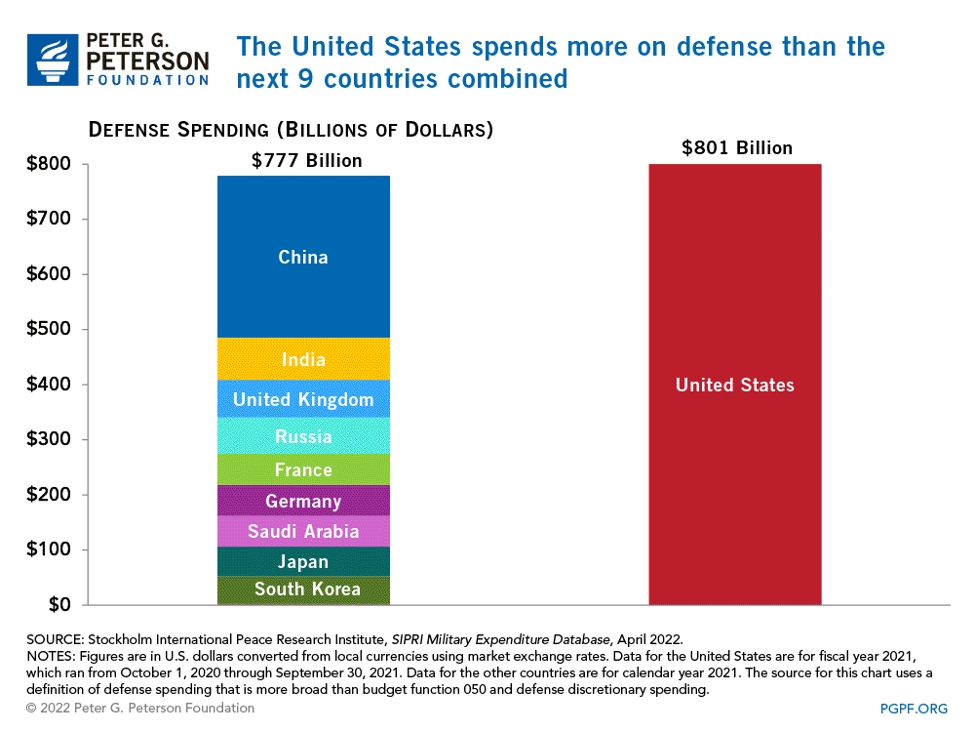

The federal government’s military budget currently comprises about 10 percent of the federal budget and nearly half of all discretionary spending. For comparison, only about 0.25 percent of the federal budget is spent on agriculture. While it can be argued that monetary support for the military increases national security, it can also be argued that improving national food security plays into this as well. A nation with higher rates of food security correlates to greater security on other fronts as well. Food security is characterized by three major components: food availability, access and utilization. While the link between food security and political stability is complicated, it is surely an intricate relationship – during the 2007-2008 food price crisis, soaring food prices triggered violent riots in over 40 countries.

If the federal government were to allocate some of the funds reserved for military and defense towards agriculture, they could pay for young farmers’ college education while incentivizing them to get more involved with farming.

The U.S.’s military budget currently sits at just above $800 billion, which is more than nine other large countries combined. The second largest military budget is China’s, which is under $300 billion. Therefore, we could decrease this budget and allocate some of those funds to small-scale agriculture subsidies and investing in the next generation of small-scale farmers.

A higher budget for agriculture would also have other benefits that could have a positive impact on the industry at large, contributing to greater interest in farming and agriculture from the younger generation. An example of this would be more financial support for organic and regenerative farming practices. Monocropping, a practice commonly employed on larger industrial farms (including both corporate and even some larger, non-corporate family farms) depletes the soil’s nutrients and degrades its longer-term viability. If the government were to offer additional subsidies for those who would employ more sustainable practices, more farmers would invest in the future and contribute to the industry’s stability. Many 18-year-olds out of high school may choose to enlist in the military due to the stability it provides – the government supports them, their college is paid for and they are paid additionally beyond just their tuition. However, for comparison, the government does not invest any additional resources into incentivizing new farmers to join the industry, nor does it provide any promise of financial stability.

While the two programs would not be identical due to the different demands and constraints of each field, a university program that incentivizes younger generations to start farming could still provide greater financial stability than is inherently offered to fresh high school graduates. Even offering to pay for young farmers’ college tuition gives them the opportunity to try their hand at the field without necessarily having to sacrifice years of time to the profession. If they decide that farming is not the path for them, they can use their education investment to pursue another career path, and the farms have benefited from their labor.

To keep farming alive and prosperous, it is imperative that we invest in the future of agriculture: more sustainable methods, higher wages for workers, and, overall, a more promising tomorrow.