For the 27th annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27), world leaders convened in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt last week to discuss the world’s progress in the fight against climate change. Some of the largest emitters of greenhouse gasses, China and India included, opted not to attend. President Biden, leader of the second largest emitter, did attend. Addressing the conference, President Biden boldly proclaimed, “I can stand here as president of the United States of America and say with confidence, the United States of America will meet our emissions targets by 2030”.

It’s worth examining the veracity of his statement, and the Biden administration’s overall track record on climate change action. It is not news to say that climate change represents an existential threat to humanity. So given its severity, is the United States doing enough to combat and address climate change?

The Biden administration’s efforts thus far on tackling climate change can be split into two key categories: revoking/remediating the damage done by the previous administration and passing new legislation. President Biden has done well on the former but could stand to do more on the legislative front.

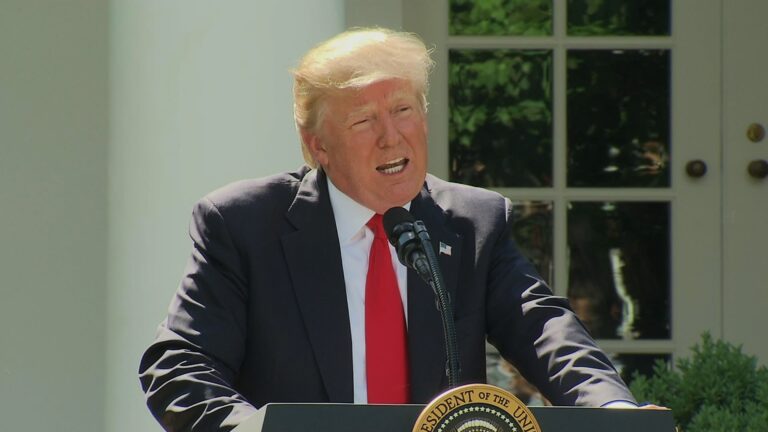

Much of President Biden’s first 100 days in office have been spent rescinding or overturning Trump’s policies. During the former president’s tenure in office, environmental regulations and protections took a backseat to profiteering. The Trump administration rolled back over 100 federal environmental regulations, which collectively had the potential to add an estimated 1.8 gigatons of additional CO2 into the atmosphere by 2035. Although Biden’s handling of this was less about active good governance and more about damage control, the Biden administration should nonetheless be lauded for its attempted minimization of the harms that will be felt for years to come from the extra emissions caused by Trump’s rollbacks.

However, a return to the status quo is obviously not enough in the fight against climate change. To acknowledge this, the Biden administration outlined its climate priorities and goals, including a cut of around 50% in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and achieving net-zero status by 2050. Although constrained by a vocal Republican minority, the Democrats have been able to push through several significant pieces of legislation that either explicitly or implicitly targeted climate change.

The first piece of climate legislation was the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act signed into law by President Biden in November 2021. The IIJA was a product of polarization and an attempt to compromise. As Morgan Higman of the Center for Strategic & International Studies explained, “Shepherded by moderates in each party, the bill reflects a limited bipartisan embrace of public investment in ongoing economic and environmental challenges without the transformative urgency demanded by climate hawks.” As the bill’s name suggests, much of the IIJA’s climate provisions come through infrastructure investment. The bill apportions $7.5 billion in funding for building a network of electric-vehicle charging stations, $65 billion for clean energy investment, and $110 billion in our public transportation infrastructure for its climate-related expenditures.

The investments made by the IIJA can be thought of as bandages over a gaping wound— it can help stem the bleeding, but only to a certain point. The main problem with the IIJA, at least from a climate perspective, is that it functions as a long-term answer to a problem that requires a quick and timely response. The goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 and a 50% reduction by 2030Higman went on to explain that, “Biden’s core climate commitments, a 50–52 percent reduction in greenhouse gases (GHGs) by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050, cannot be reached with business as usual—they require bold action. But the IIJA… is unlikely to beget more than incremental progress in emissions reduction and technological leaps in some sectors.” The bill certainly was a step in the right direction—helping to modernize the United States’ aging infrastructure and curbing the transportation sector’s impact on the environment as the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. But it’s not enough to reach net zero by 2050 and it’s certainly not enough to cut emissions by 50% by 2030.

Fortunately, another piece of legislation managed to break through Republican opposition and was signed into law in August: the Inflation Reduction Act. The IRA includes the largest ever U.S investment in climate change action, at around $369 billion. The money will be used, among other things, to expand tax incentives for clean energy development, invest in the infrastructure necessary to support the transition to clean energy, and help the agricultural sector adopt more climate-friendly methods. Like the IIJA, the IRA carries the promise of modernizing our systems and infrastructure to be more climate-friendly. The U.S Dept. of Energy estimates that together with the IIJA, the IRA is estimated to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030.

Of course, the elephant in the room is the elephant in Washington. The IRA contained multiple capitulations to the fossil fuel and coal industries. Even with those capitulations, the bill received no Republican support in either of the chambers, passing with the muster of the entire Democratic party, solely thanks to Joe Manchin’s last-hour acquiescence. Even with the Herculean effort required to pass the IRA, the U.S. is still not on track to reach the intended 50-55% emission reduction by 2030.

It can be argued that the perfect should not be made the enemy of the good in this case: the IRA and IIJA may not allow us to fully address the Climate Crisis on its own, but it gets us closer at around a 40% cut in emissions after all. It’s worth noting though that both the IRA and IIJA endeavor to achieve emission reductions through carrot methods—tax incentives, investment opportunities, etc. Carrots are obviously more attractive than sticks, and with Manchin in the pockets of the coal industry, it’s essentially the only policy tool the Democrats have for now. But ignoring the stick side of policy—increased regulations, cap & trade systems, etc —hampers the effort by removing half of the policy tools available.

President Biden should help fill this gap through executive action. As the head of the administrative branch of government, he can pass executive orders regarding EPA regulation and enforcement. While his predecessor used this power to dismantle years of climate progress and deal irreparable harm to this and future generations, Biden can use it for good. The President did well to reverse much of this, but it’s not enough: Biden needs to strengthen environmental protections to fulfill his campaign promises and reach net zero by 2050