“It doesn’t matter. They’re not going to protect us.”

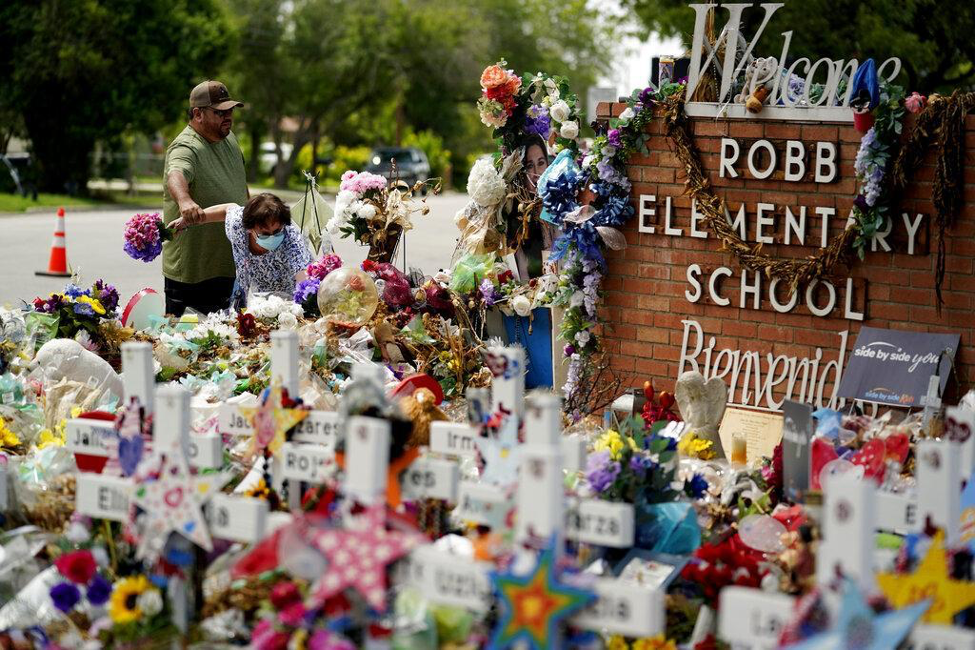

This is how Zyon Martinez, a second grader and survivor of last May’s Robb Elementary School massacre, reacted to the prospect of an increased police presence in Uvalde, Texas elementary schools as the new school year began this September.

Martinez is undeniably referring to law enforcement’s fatal decision to stall for an hour and 17 minutes before confronting the active shooter, who was left alone inside two interconnected elementary school classrooms containing students aged nine through eleven, as well as three teachers. Hundreds of local police officers, border patrol agents, Texas state troopers, U.S. Marshalls, and other state and federal law enforcement agencies responded ineffectively.

It should be acknowledged that properly enforced “red flag laws” or other gun control measures could have prevented the shooting entirely. The gunman was nicknamed among his peers “school shooter,” and had a recent social media history of sharing suicidal intentions, violent sexual and beheading videos, footage of a dead cat in a plastic bag and his plans to be “all over the news.” Despite these obvious red flags, the shooter was able to purchase two semi-automatic rifles for his 18th birthday. A quick social media background check, in line with proposed red flag law protocols, could have potentially prevented the shooter from acquiring deadly weapons.

The public policy failure that ultimately stands out in Uvalde however, is the systemic incompetence of law enforcement responders throughout a wide array of state and federal agencies.

The reality of gunshot wounds is that, unless located in specific vital organs such as the heart or the brain, they rarely lead to immediate deaths. Depending on the severity of their injury, victims can take time to bleed out and eventually die. This is why it is “active shooting” protocol for law enforcement to rush active shooters as soon as possible. Doing so can save others from being shot and accelerate victims’ access to medical attention.

Instead of rushing the gunman immediately, given that two groups of police officers were in the building within three minutes, law enforcement chose to treat the situation in Robb Elementary as a “hostage” scenario. In infuriating hallway footage released by Austin local news, officers are seen sprinting away from gunfire to the opposite side of the school corridor. Officers then stalled for an hour and 17 minutes even as more and more state and federal law enforcement agencies arrived on the scene. Several children made phone calls throughout the standstill pleading for help, indicating that at least multiple children in the classrooms were alive. At one chilling and telling moment, officers shouted to children inside the classroom, suggesting they call out if they needed help. One young girl did so, revealing her hiding position, and was quickly shot dead. At any point, law enforcement could have engaged the shooter.

Many police officers spent the duration of the massacre outside of the school building, preventing Robb Elementary School parents willing to confront the shooter themselves from entering. While young elementary school children were dying, hiding and playing dead for 77 minutes between the two interconnected classrooms, a rapidly growing police presence stood idly by.

After a border patrol tactical unit finally breached the classroom and neutralized the gunman, one teacher died in an ambulance and three children later died at the hospital, all but confirming that more victims could have survived if police had entered sooner. The failures of the responding officers on all fronts is almost incomprehensible.

“He could have been saved… The police did not go in for more than an hour. He bled out,” said the grandfather of ten-year-old Xavier Lopez, a victim who later died at the hospital.

The only officer to have been fired several months later has been Pete Arredondo, the school resource officer who initially responded and who refused to enter the classroom or relinquish duty to a higher-ranking agency. Finally, five state troopers from the Texas Department of Public Safety are being investigated for their conduct, two of which have been suspended with pay.

It is correct for Arredondo to be fired because if he had led the original two groups of officers into the classrooms, within three minutes of the initial shots, many more lives would have almost certainly been saved. Arredondo’s lawyer, despite the fact that there were already multiple colleagues of the school officer on sight, argued that rushing the classroom would be “tantamount to suicide.” Before taking such defenses seriously, consider if America would have accepted 9/11 responders merely waiting outside the collapsing skyscrapers.

What is crucial, is that the higher-ranking state troopers and other law enforcement agencies face scrutiny as well. Despite Arredondo’s failure to relinquish duty on-sight to state troopers, chain-of-command policies must be unified among all law enforcement agencies, so that when the failings of lower-level officers occur, state and federal agencies are able to quickly take over and neutralize the threat.

We do not yet know the conclusions to the investigations into the five state police officers.

Surely, some of the 376 officers that responded were brave enough to run into the interconnected classrooms and kill the shooter sooner. One officer who tried to enter the class several minutes into the shooting was reportedly prevented from doing so by other law enforcement responders and was not followed by any of his colleagues. The reasons for the Uvalde failures are thus systemic, and a single school resource officer taking the entire fall for the negligence of several state and federal law enforcement agencies is insulting. Holding the leaders of the responding agencies accountable and revamping chain-of-command policies through federal action is paramount to saving more lives during America’s inevitable future school shootings.