Like many of my colleagues here at the Zeitgeist, I followed the twists and turns of the 2020 election somewhat obsessively. In addition to keeping tabs on polls and forecasters (i.e. psephologists), I added a new ingredient to the mix—political prediction markets. Like the Needle from the New York Times, tracking swings on Predictit was a flawed but useful exercise.

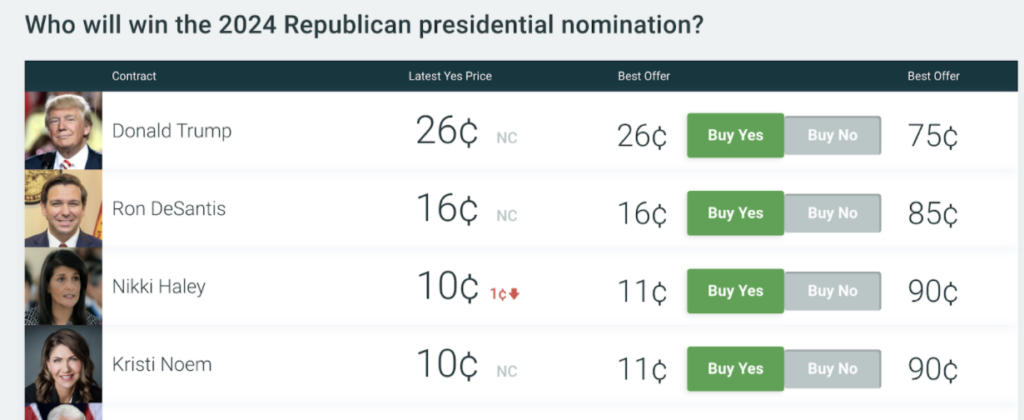

Prediction markets are a cross between a stock market and a sportsbook. On the most popular US platform for politics predicting—Predictit—traders can buy “yes” and “no” shares on the next mayor of New York City and the composition of the Cabinet on March 31 among dozens of other events. When Biden won the general election, all “Biden: Yes” shares in the general election market paid out at $1, as did all the “Trump: No” (and “Gabbard: No”) shares. So, if in October “Biden: Yes” shares are selling for 60¢, that indicates the market’s belief that Biden has about a 60% chance of becoming president.

These Predictit probabilities are useful for the same reasons that polling is useful. In fact, archival work by economic historian Paul Rhode shows that formal prediction markets served as a precursor to political polling in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. The total bets placed on the 1916 election exceeded total spending by campaigns, and the odds from one market (set up on the Wall Street curb) were quoted almost daily in the New York Times.

The theoretical case for a prediction market is similar to the theoretical case for any other market: the potential to aggregate information from a diverse group of participants, whether it be one person’s analysis of FEC reports or another person’s inside scoop on Georgia politics. If you knew something useful not reflected in the market, you’d trade on that information until it is incorporated into the price (and you’d be rewarded by profit). Like in finance, the degree to which this “efficient market hypothesis” holds is a hotly-contested topic. For instance, some behavioral economists have examined whether bias towards longshots can systematically skew prediction markets.

The structure of Predictit also creates additional frictions that detract from its goal. Predictit is a scaled-up version of the Iowa Electronic Market (IEM), meaning it’s run by New Zealand academics for educational purposes. Per Predictit’s agreement with US regulators, each person is only allowed to stake $850 on any one question, and (unlike IEM) Predictit charges sizable fees on both profits and withdrawals to fund its operations. As University of Michigan economist Justin Wolfers detailed in a thread on the eve of the election, these and other hurdles mean it is often not worth it to correct even major mispricings. The most extreme example of Predictit’s shortcomings came after the election, when—as late as December 13—Biden was only given an 85% chance of winning the election. While the lag may partially reflect unwavering commitment by Trump loyalists, its longevity is largely the result of Predictit’s inefficiencies (full disclosure, I made $7 last fall by helping to correct this mispricing).

Despite the imperfections of current implementations, prediction markets can still add useful information to the public sphere. In a pre-election talk, Wolfers noted that, although there isn’t a clear consensus, there is some evidence (e.g. studies collected here by Dartmouth political scientist Brendan Nyhan) that prediction markets can outperform polls. But Wolfers also stressed that the two approaches are complementary—Predictit prices often update based on new polling. One study comparing the 2008 FiveThirtyEight model to prices on IEM found that, relative to poll-based models, markets were particularly useful early in an election cycle and in less-scrutinized elections. And independent of accuracy, another advantage of prediction markets is that it updates in real-time—it takes days after a debate to get polls on its effects, but you can try to get a rough picture of the state of the race as the candidates are talking.

Creating a more functional prediction market could provide new insights not just for the political horse race—you can run a prediction market for any issue you can operationalize, from atmospheric CO2 levels in 2030 to the pace of the vaccine rollout. Companies like HP and Google already use internal prediction markets to forecast future revenue and product launches. Markets aren’t perfect, but neither are polls or experts, or any of the other methods we currently have to make decisions about the future.

Some might be leery of promoting gambling on elections or vaccines. I understand the concern. But the stock market doesn’t appear to be any less of a gambling enterprise—Bloomberg’s Matt Levine attributes many recent financial abnormalities (e.g. Gamestop, Hertz) to “boredom” and people betting on companies in lieu of sports. This doesn’t then mean that we should close the stock market, because the market (theoretically) still provides useful information about companies and capital allocation.

Considering the billions of dollars in financial capital and innumerable hours of human energy that are poured into each election cycle (and into polling each election cycle), even a slight improvement in the allocation of volunteer time and donor money could have massive ramifications. A functioning prediction market—with higher market ceilings and fewer fees limiting liquidity—could become a valuable supplement to existing tools for political actors and enthusiasts alike. If achieved though, the ability for political prediction markets to gauge elections early in a cycle could help partisan actors invest in the most promising candidates and private actors to prepare for the future (or even hedge their risk to an extent). If the principle were extended to the policy realm, the returns to aggregating information on economic, demographic and environmental forecasts could be even greater.