“Laboratories of democracy” are a distinctive feature of the American system. The phrase traces back to a 1932 dissent by Justice Louis Brandeis, who wrote that “it is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”

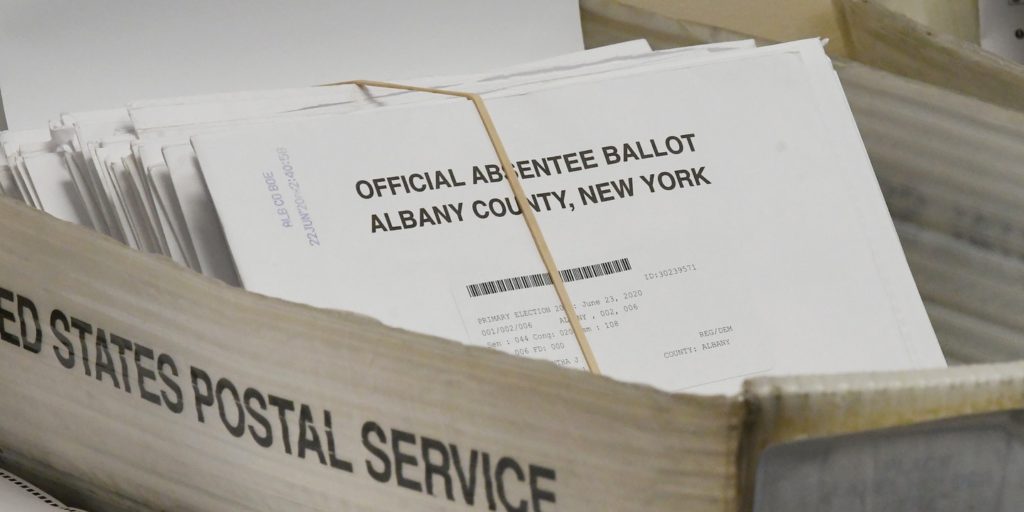

After the pandemic made voting a public-health hazard, states scrambled to implement mail-in and early voting. Some states, like Oregon and Colorado, had extensive experience with mail-in voting and were ready for the pandemic. Most states however were forced to overhaul their election systems with little federal guidance in a matter of months.

The extremely varied approaches taken by states and localities will make for fascinating political science papers. But when it comes to election administration, one state’s experimental design is not “without risk to the rest of the country.” A debacle in a single state could undermine trust in the entire election and set our democracy ablaze. In the 2020 election, quite a few states and cities have combustible election systems, yet officials from both parties are failing to put out the embers before they potentially burst into flames.

Source: FiveThirtyEight/ABC

Take, for example, New York City. The Democratic stronghold has provided plenty of fodder for Trump’s (mostly baseless) claims that mail-in voting is susceptible to fraud. In the July primary, the Board of Elections mailed 34,000 ballots only one day before the election. The postal service then failed to postmark many of the returned ballots, thereby casting doubt on any ballots arriving after election day. All told, a federal judge wrote that “systemic failures” invalidated nearly one-in-ten absentee ballots, and in two closely watched congressional primaries, the winner was not known for over six weeks. In the general election, New York is at it again, incorrectly labeling 100,000 ballot-return envelopes, and hosting hours-long lines at early voting locations.

New York’s Board of Elections is “notoriously incompetent,” but New York’s experience features many of the challenges faced by local officials nationwide. Firstly, it highlights the pivotal role of the Postal Service in ensuring a smooth election, and it reminds us of the magnitude of the task at hand—the city received ten times more absentee ballots than usual in the primary.

It also foreshadows the inevitable role of litigation, as ballots are disqualified for oversights both within and outside of a voter’s control. When combined with the drawn-out counting process, the high number of anticipated mail-in ballot rejections create ample source material to contest the results and pursue litigation.

In fact, hundreds of cases have already been filed. In a parallel to the 2000 election, these cases often feature Republicans seeking to maintain or strengthen voting regulations and Democrats seeking to expand vote-casting and vote-counting opportunities.

In recent days, the Supreme Court has weighed in on three cases where lower courts allocated more time to receive mail-in ballots. Chief Justice John Roberts sided with the court’s three liberal justices in allowing a Pennsylvania ruling giving ballots in that state postmarked by election day three extra days to be received. A similar 4-4 decision allowed six extra days in North Carolina, while Roberts sided with conservative justices in blocking an extension in Wisconsin.

In a supplement to the Wisconsin decision, Roberts explained his view that while the Pennsylvania order was from the state Supreme Court, who has final say over state law, the Wisconsin order represented overreach by the federal judiciary.

This deference to the states is correct as a matter of legal doctrine, and allowing states to interpret state law is an important principle. But leaving the choosing of electors up to state legislatures may be impractical and problematic, especially in this moment of upheaval.

Local administration of elections has created a highly fragmented and diverse system at both the state and local levels. This fragmentation comes with some benefits: it limits the potential for political interference by the incumbent president, as well as the potential for foreign interference—hacking at scale is less feasible if every county is using different voting machines.

On the other hand, the lack of regularity and oversight of state election administration threatens the stability of our voting system—because impropriety and disenfranchisement anywhere is a threat to election legitimacy everywhere. Five Trump ballots found floating in a river—even in the Hudson River—could throw the election’s legitimacy into doubt (even wild allegations of ballots dumped in a river have lasting effects on voter confidence). So much of our election runs on trust, and faced with a president intent on sowing distrust, our faith in elections is likely only as strong as the system’s weakest link.

New York’s primary debacle, in conjunction with “meltdowns” in Iowa, Wisconsin, Georgia and elsewhere, has raised serious concerns for the general election. But something even more troubling may be brewing in Pennsylvania—currently the forecasted tipping point. In addition to the court battle mentioned above, Pennsylvania, like New York, has many infrastructure vulnerabilities, many of which mirror our last disputed election in 2000.

Fears of Russian tampering led at least 14 states, including Pennsylvania, to mandate new voting machines with more meticulous paper trails. In 2019, one county in Northeastern PA incorrectly programmed the new machines, leading to major slowdowns and complaints of mis-registered votes, with one candidate’s votes being entirely omitted.

Decentralization could also be a major issue in Pennsylvania. The New Yorker reports that “all sixty-seven counties have different procedures for receiving and counting mailed ballots.” Similar discrepancies in recount procedure between election boards were at the core of the Bush campaign’s successful legal argument to halt recounts in Florida on the grounds that ballots were being given “arbitrary and disparate treatment.”

On top of all that, Republicans who controlled the state legislature had been arguing with Democratic governor Tom Wolf over issues like election security and mail-in expansion. Most attention-grabbing though was a bill to a “Select Committee on Election Integrity” with the power to subpoena election officials (and thus, critics say, to slow down the counting of ballots and to undermine the integrity of that process).

In some sense, Pennsylvania Republicans were using the tactics they advocated for in court to minimize the specter of voter fraud, a useful specter which has haunted them since the Brooks Brothers Riot in 2000 halted recounts favorable to Gore.

At the extreme however, what Pennsylvania Republicans seem to have been preparing for was the possibility of using our electoral devolution to brush aside the popular will. Republican Party sources told The Atlantic that “the Trump campaign is discussing contingency plans to bypass election results and appoint loyal electors in battleground states where Republicans hold the legislative majority.”

I’m a critic of “doomscrolling,” and when I first encountered these hardball scenarios, I dismissed them as liberal anxieties. That is true to an extent—the most likely outcome if polls are even somewhat accurate is an incontrovertible Biden victory. But this brazen maneuver by some state legislature would be completely legal, especially if counting delays mean that the electoral college meeting is imminent while the election’s result is unclear.

Caption: A select committee of Congressmen, Senators and Supreme Court Justices deliberate by candlelight on the outcome of the 1876 election. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Just such a crisis happened in 1876. On election night in 1876, Democrat Samuel Tilden led Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote and led the electoral college 184-165, needing 185 votes to win. The results in three Southern states and 20 electoral votes were disputed with both campaigns claiming victory. Amidst allegations of voter fraud, voter intimidation and threats of violence against Republican voters, both parties sent twenty electors to Washington who claimed to be the legitimate ones. After an incredible amount of political and legal maneuvering at the state and national level, the impasse was finally resolved through the informal compromise of 1877, where Democrats allowed Hayes to be president and in return Hayes brought about the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of the Jim Crow South.

Again, I don’t present this to you as a prediction, but rather to highlight the fragility of leaving elections entirely to the states, to manage in the manner they so choose.

Federalizing elections and instituting a national popular vote may not be the best answers, but the federal government is shirking even the duties it usually performs. The Federal Election Commission, who enforces campaign finance law, has been without a quorum for three months and counting, rendering them impotent during the most expensive election in American history.

Congress could have also done much more to help state and local governments in overhauling their election systems and to accommodate more labor-intensive mail-in ballots. While $400 million was set aside in the $2 trillion CARES Act for election related expenses, critical election infrastructure remains wholly underfunded. The postal service is on the verge of bankruptcy, and austerity measures have led to slowdowns in mail-in ballot delivery. Meanwhile, a late-April report from the NYU Brennan Center for Justice found that federal aid had only covered between one-tenth and one-fifth of the additional costs associated with a pandemic election in the key states of Georgia, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

Just as late returns from the Florida panhandle broke heavily for Bush in 2000—famously forcing the networks to retract their race calls—political scientists note that later returns have broken more Democratic in recent years than earlier ones in what they term “the red mirage.” The high volume of mail-in voting, which is expected to skew more Democratic than the election-day vote, only complicates this calculus, since some states like Florida have already started counting mail-in votes, while others like Pennsylvania will not open envelopes until election night.

All of this confusion and chaos lends itself naturally to false starts, uncertainty—and one or both candidates to declare victory prematurely, casting aspersions on the rest of the vote. The constitutional crises of 1876 and 2000 remind us that what happens next is not totally uncharted territory, but that makes it no less daunting.

If we have a disputed election, it will be up to Congress, the Supreme Court and the federal judiciary to sort out an incredibly messy situation. If that situation comes to pass, these institutions will be forced to wonder whether they could’ve done more to stabilize the election in the first place.