I don’t often put much faith into business as the driver of society’s moral conscience. I still don’t. So why are oil companies and lobbying groups starting to take action against the threat of climate change? How does this present itself across the industry and our globe?

Hurricanes, wildfires, record droughts… the threat of climate change is more apparent and widely felt than ever. Yet, when considering how much of this economic devastation has reached the oil industry, climate change hasn’t caused them damage. The two main concerns climate change causes for oil executives are public image and environmental regulations affecting their bottom lines.

While giant oil companies such as Exxon and British Petroleum have publicly stated their support for combating climate change by making green energy a priority (including supporting methane regulations as “the right thing to do”), smaller oil companies have fought Obama-era regulations tooth and nail. Exxon Mobil could stomach expensive regulations, but the Colorado Oil and Gas Association— an industry lobbying group— couldn’t afford investing in methane-leak-detection technologies, much less carbon costs.

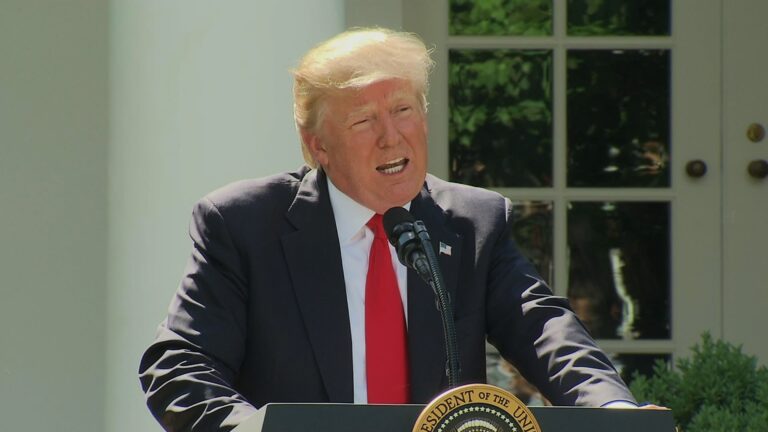

The Trump administration overturned Obama’s environmental protection policies and welcomed the accompanying argument of oil and gas lobbyists: companies pretend to have already had an incentive to prevent methane leakage in their drilling because it is a valuable resource, thus a regulation to ensure companies did so was unnecessary. However, a secret recording from oil lobbyists, reported by the New York Times, reveals that their personal beliefs contradict their public claims. The argument was moot considering how much natural gas (a “bridge fuel” to help companies shift away from coal and toward renewable energy) they wasted. Many smaller oil companies were becoming seriously concerned with their own practices such as “flaring”— where natural gas was burned off because of its lower economic value— and with how they can appeal to a younger generation that has become increasingly concerned about climate change.

While corporate America has a nasty habit of planning for the short-term rather than the long-term, climate change has finally entered the limited radar of their lobbyist groups, and we can see this concern from businesses turning into actionable (albeit incremental) steps toward joining the fight. The Wall Street Journal reported this shift by focusing on the relatively new statement on addressing climate change from one of the “country’s most prominent business groups [Business Roundtable][…] represent[ing] the consensus of more than 200 members spanning every sector of the economy.” While the statement doesn’t wholly stray from the norm, (businesses have advocated for a carbon price before), the WSJ underscores the significance of businesses endorsing the revenue from the price go not into tax cuts or household checks, but for government programs addressing climate change.

This attitude shift from Business Roundtable, though welcome, has come about four years too late. So far, Trump has reversed well over 100 environmental rules. There is the more obvious — approval of drilling in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge— and then there is the more discrete: repeals, replacements, and withdrawals of “emissions rules for power plants and vehicles”, “protections for more than half the nation’s wetlands,” and “legal justification for restricting mercury emissions from power plants.”

Some of the largest voices advocating for these reversals have been business lobby groups. Now, while Business Roundtable isn’t going to push for the Green New Deal, under Biden’s climate agenda they would “play a significant role both in shaping specific proposals and influencing individual legislators.” This group’s membership, spanning both large and small companies, means they are limited in their advocacy efforts. (The small companies ensure they haven’t “endorsed a carbon price.”) Additionally, other groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and National Association of Manufacturers “helped kill Congress’s attempt to create a national emissions trading system [years ago].”

The Wall Street Journal underscores the main reason companies now care about pushing against the Trump administration’s rollback of Obama-era regulations: “China, Japan, the European Union and Britain all have, or plan to have, either a carbon tax or an emissions-trading system. Without something similar, U. S. companies risk being penalized abroad.” The initial controversy over whether or not carbon taxes should be instituted included the question of how carbon taxes would affect the international competitiveness of our energy industries. A possible solution would’ve been international coordination to ensure the market remains fair while countries institute their national carbon taxes. As coordination seems unlikely now, the U.S. is just stuck playing catch up.

So, how large is this gap in regulations between the U.S. and the rest of the globe? Let’s focus on contrasting Europe and the U.S.. While the U.S. and E.U. were relatively neck in neck in the strictness of their regulations in 2014, the U.S. has been moving backward since 2016 while the E.U. doubled down on its goals. From a “new financing mechanism to boost renewable energy” projects to transitioning coal regions into sites for other purposes, the European Union has guided it’s corporations into moving into natural gas and then renewable energy.

Now with the pandemic, it has also become more economical for the oil and gas industry to double down on its efforts to diversify to lower-carbon energy sources for post-pandemic recovery. There are multiple strategies to achieve these goals; the NYT highlights the quite noticeable difference between big American oil companies and big European oil companies.

Exxon Mobil and Chevron has been “doubling down on oil and natural gas and investing what amounts to pocket change in innovative climate-oriented efforts like small nuclear power plants and devices that suck carbon out of the air.” Their first priority remains meeting energy demands, but to boost their public standing they invest in endless research projects hoping for a miraculous breakthrough. European investors have little faith in the American strategy and “even some Wall Street investors” have divested from Exxon Mobil and Chevron.

BP CEO pushes aggressive plans to shift into renewable energy. PHOTO: Toby Melville/Reuters Photo courtesy of NYT.

British Petroleum has been singled out as “the standard-bearer for the hurry-up-and-change strategy”. They’ve reported huge losses in recent months and there’s been huge skepticism from investors on the new CEO’s ability to accomplish their aggressive plans, but still, BP has been acquiring more risk and moving away from its largest revenue stream—oil—to explore renewable energy and low-carbon sources. They have attempted this same “pivot” before. “More than a decade ago, it rebranded as “Beyond Petroleum” and committed to generating more renewable energy.” That failure is hurting their image now, but potential success would set a strong example for other companies that prioritizing the fight against climate change can be profitable. As the industry scrambles to deal with the dramatic drop in demand for oil right now, the viability of this outcome is stronger than ever.

Other European companies such as Royal Dutch Shell, Eni, and Total are moving slower, but with the same goals as BP. If American oil giants take note from the E.U. and European energy companies, working in conjunction with the new administration to achieve more ambitious goals, we might see a serious dent in greenhouse gas emissions.

As Metronome, (a timer for when the effects of climate change become irreversible), in downtown NYC counts down, the Trump or Biden administration come November has to ramp up regulations, push businesses to stay this green path, and incentivize investment in renewable energies. If America wants to hold its head up on the international stage as a global leader of industry, we need to catch up to our peers.