At the start of the 20th Century, China and India were in the same economic positions: both nations have their own share of troubles trying to boost their respective national GDPs whilst trying to build a more robust system of accountability for their banks. The majority of banks in both nations are largely owned by the state. By the 1990s however, China and India started to diverge.

Deep economic reforms made by the Chinese government gave rise to its strong and consolidated banking core with the “Big Four” banks, which are now the largest banks in the world. India, on the other hand, went on a completely different trajectory. There were more than 27 different state-owned banks scattered throughout the country in 2017. Now there are 12: all of them have gained a reputation for inefficiency and a chronic need for recapitalisation.

Despite the myriad of challenges facing India’s core financial system, the three of the most pervasive problems–lending for political interest, a lack of political will to address banking mismanagement, and the government-backed soft-budget constraint–there could be formally solved with privatisation. This is a sentiment expressed in both academic and professional circles. The most notable advocate for privatising banks and the former deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Viral Acharya, just so happens to be a current professor at our own New York University.

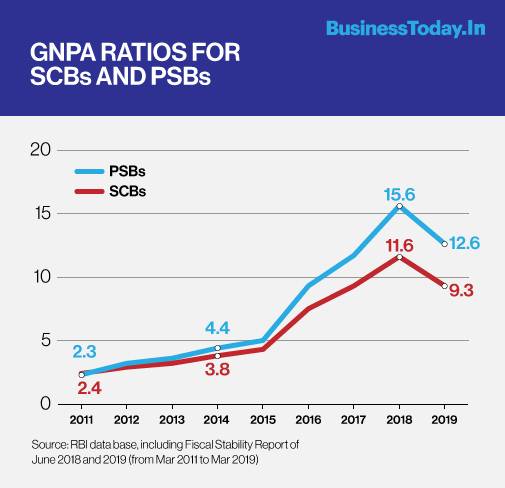

The most obvious problem that arises with a state-owned banking system is that it creates an environment for the politically motivated appointments of bankers. The people at the top of the state-owned banking system are, therefore, not there because of their sharp business acumen or expertise, but rather because they possess a strong connection with the politicians in charge. Needless to say, this leads to careless lending practises. This then results in a pile-up of non-performing assets (NPA), in this case, debt and interest, that is not generating any revenue for the banks. The NPA ratio is reported to be 12.2% in March 2019 for the Reserve Bank of India, which is the fifth-worst ratio on the planet at the time of writing. In contrast, the NPA ratio for China and the US stands at just under 2%. India’s fractured politics exacerbate the loan crisis so terribly that it’s bringing the entire Indian economy to a standstill.

Indeed, this is exactly what we see. In 2018, President Modi publicly announced that he will forgive more than an estimated 50 billion USD worth of farmer’s debt in an effort to win on his political campaign among rural voters. Despite President Modi’s best intentions, he is treating a symptom of the bad banking system, not the cause of it.

The entire agro-industry, along with steel and housing industries to name a few, have all been impacted by weak banks. One question that comes to mind upon seeing Indian President Narendra Modi’s announcement is: how did farmers’ debt get up to 50 billion US dollars in the first place? The answer is bad loan practises, or rather, more specifically, haphazardly loaning money to known risky borrowers. There were no mechanisms to keep state-owned banks accountable or verify their credits until recently, but the damage had already been done. Furthermore, transparency and keen paperwork urged by the state government will certainly help keep banks honest but transparency does not guarantee accountability.

The question of whether or not this has fixed the underlying problem remains. The problem of borrowers not being able to pay back debt is not the issue, this is inevitable in the financial world; every bank operates on the assumption that there are going to be a few loans that won’t be paid back. The problem is the universality of bad borrowers across all of state-owned banks. The issue is not the number of state-owned banks but within state-owned banks themselves. Whenever a bank is under-capitalised, the government is always standing by, ready to step in and recapitalise it. Unsurprisingly, this has played out so many times in recent years that government relief packages have lost their novelty and urgency. This is a textbook example of moral hazard: Disregard for one’s risk knowing that one is protected from the consequences. This is why privatisation is the answer. Privatising these state-owned banks would incentivise the more prudent measures when it comes to lending money; privatising would also help send the message that when these banks fail, the government won’t be there to bail them out.

The argument for privatisation in this case is not made on grounds that private banks are more efficient, but on grounds that a fundamental separation between politics and banking is necessary for enforcing accountability. Inefficiency and a lack of transparency could be found almost everywhere in developing countries and even in some developed ones. However, what makes India’s debt crisis particularly severe is that there is a lack of political will to mobilise a response. According to the Wall Street Journal, the real issue facing India is its “largely state-owned banking system takes orders from politicians rather than allocating capital efficiently based on a prudent assessment of risk.” In effect, the issue is that, despite acknowledging the loan crisis, the crisis continues to worsen because of a simple conflict of interest.

There is a systemic lack of cohesive financial governance to respond to a crisis lies at the heart of its debt problem. Dumping massive capital would only do so much to offset bad loans, so the underlying corruption and mismanagement need to be fixed. Privatising ensures that banks are going to be more efficient with their investment and savings strategy whilst reducing costs. The Indian government would not only eliminate conflict of interest when going after banks for bad practises, but it would also mobilise responses much more readily and willingly.

Despite the looming debt crisis, India has taken great strides to improve its financial system. In a study done by MDPI, Indian state-owned banks have become much more competitive after the implementation of new banking legislation, such as Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code of 2016. However, there is still a lot of work to be done. The reality is that the government can’t adapt fast enough to get out of this economic slump that started in 2014. The talks of merging and consolidating India’s state-owned banks are themselves short term solutions. Most of the non-performing assets are concentrated in state-owned banks and as a result, they are hit harder than private banks during a crisis. Private banks have fewer bad assets and function as a self-supporting entity, granted that the government would need to ensure transparency as they have always done. The case for privatisation in India’s banking climate should not be seen as a cure-all to all of India’s woes but instead, a commitment towards accountability which needed to be followed by new banking innovations.

Fortunately, there are dozens of potential solutions India can look towards for inspiration as an alternative to its current financial model: from adopting features of Islamic banking to encouraging more microfinancing in lieu of current state-owned bank heavy finance model. For an effective long term fix, these deep-seated political and economic issues have to be addressed along with India’s insistence on a state-owned banking system.

Dan Song