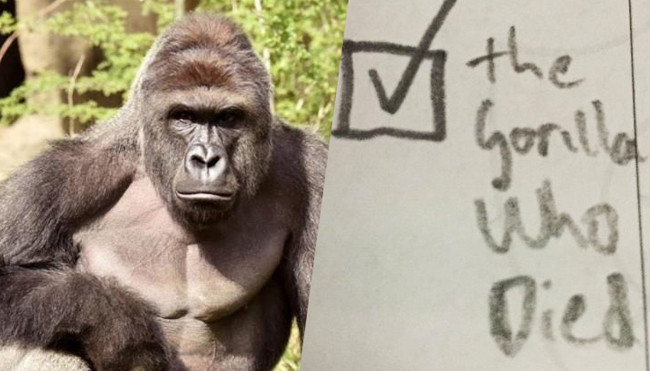

Internet memes have become a force, politically and culturally. They are not only a device and a medium for political discourse, but they also impact the offline world in a variety of ways. It was during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election that memes began to arguably impact politics offline. Just look at Harambe the gorilla (shown in the cover photo) receiving votes, at fake presidential candidate “Deez Nuts” pulling nine percent in a North Carolina primary poll, or at Pepe the Frog (a meme character who had become a symbol of the “alt-right”) becoming classified as a “hate symbol” by the Anti-Defamation League. Even then-candidate Donald Trump tweeted memes, one of which is an image containing a version of Pepe made to resemble him.

N.Y.U. alumnus Calvin Tran, who is the founder and head of the media outlet NODEHAUS Media, has thoughts on memes and their growing influence on politics and culture.

DB: How would you, in your mind, define a meme?

CT: So “meme” comes from Richard Dawkins [the evolutionary biologist] actually. . . . He wrote a book in the 70s talking about how genes operate by mimicking themselves. That’s the biggest feature of genes: [There are] genetic combinations that they replicate and [that] they mutate. And so he looked at ideas—people sharing ideas and creating things—it also replicates in the sense that if I give you an idea, the idea is replicated into you and it may mutate in the sense that you may take a different part of the idea that I give you. So what he called that—the replication and mutation of ideas—to be “memes.” So “memes” in that original sense is an idea that people share. So in [the Internet] sense, a meme is simply an idea that we pass around and has been put onto a hyperdrive because of the Internet.

DB: To what extent do you believe memes have an impact on our politics today?

CT: Political memes are probably the most impactful medium we have now. We’ve had changes in technology… having a written language, that’s one thing; having the Gutenberg printing press, another; having television, radio, every other technological advancement radically changes our culture, and therefore our politics. So, the Internet has done the same thing, but if we look at the difference between the printing press and internet memes, the printing press, to print out a book, you had a lot of hurdles. So, it democratized things, it democratized the Christian religion and all that kind of stuff; but it’s still the case that it would take several years.

With internet memes, I mean it’s such a radical shift, and we saw that in 2016—one hundred percent. I believe Harambe was one of the most impactful memes in an international sense, which launched a lot of populist fervor. Because—as we saw—we were forced as, I guess, a community to listen from CNN and NBC, to be angry at this happening for 48 hours. And our reaction, as an online community and as an online, internet culture, was absolutely against that. And so that impact alone—the fact that that happened—reflects that our culture is affected by our political memes.

DB: What about the election itself?

CT: When you look at the fact that Donald Trump destroyed two political dynasties in one term and then won an election. [That’s] because political dynasties reflected an old, establishment, and institutional form of our politics; whereas Trump was able to play with his brand in certain ways that allowed him to leverage the internet community.

I mean one thing is—let’s look at Hillary’s campaign. She just did so many things that were illiterate of the Internet—internet-illiterate. Whereas Trump wasn’t. He was able to utilize the internet community. The second point of evidence here is that [University College London] recently did a study on the origins of memes. So, they used computer programs to create a digital footprint for memes and track where they came from. And they basically found that . . . a vast majority of them came from basically just two communities, and they happen to be some of the most politically right-wing. [This] points us to the fact that it was the right wing of politics that had the advantage online, and I don’t think you can divorce that from what happened in 2016.

DB: And what is the “Great Meme War?”

CT: So, already political analysts phrase elections and politics as a “war.” What happened in 2016, though, was that it finally disseminated itself into the Internet. And particularly the right wing of politics—the more savvy wing of politics—phrased 2016 as the “Great Meme War.” They saw it as [if] they were on the front lines of creating new content and spreading ideas around, and it felt like a cultural war that they were winning. And we’ve called it a culture war for so many years, you know, between conservatives and liberals. So it was just a culmination of all of our cultural sparrings over the last few decades into one gargantuan moment between a literal Clinton and someone else who was not at all supposed to win in any sort of way—Donald Trump—and all the things that had to happen throughout his campaign that year. So it felt like an absolute political revolution, a political revolt—all those kinds of things culminated into what was this great war, the Great Meme War—2016. And this is going to continue as a trend in politics from here on out; 2020 is going to be a meme war as well.

-Douglas Braff

Note: The director of “In the Zeitgeist,” Jana Cholakovska, and staff writer Douglas Braff will be guests on NODEHAUS’s new podcast “Memes of Our World.” You can check out snippets from previous episodes of the podcast here.